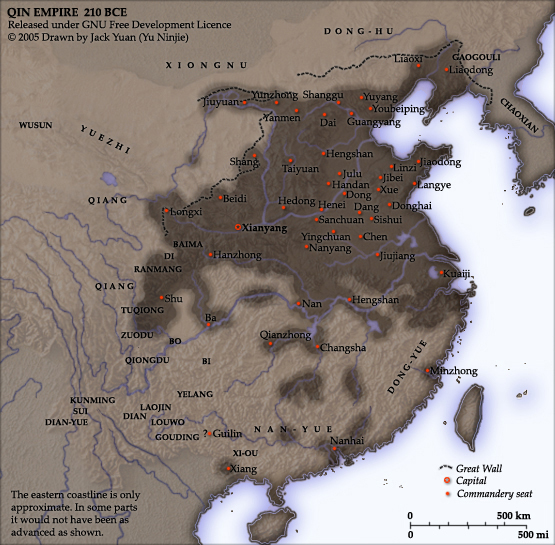

Qin dynasty (Chinese: 秦朝; pinyin: Qín cháo; IPA: [tɕʰǐn tʂʰɑ̌ʊ̯]) was the first dynasty of Imperial China, lasting from 221 to 206 BC. Named for its heartland of Qin, in modern-day Gansu and Shaanxi, the dynasty was formed after the conquest of six other states by the Qin state, and its founding emperor named Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor of Qin. The strength of the Qin state was greatly increased by the Legalist reforms of Shang Yang in the fourth century BC, during the Warring States period. In the mid and late third century BC, the Qin accomplished a series of swift conquests, first ending the powerless Zhou dynasty, and eventually conquering the other six of the Seven Warring States to gain control over the whole of China.

During its reign over China, the Qin sought to create an imperial state unified by highly structured political power and a stable economy able to support a large military.[1] The Qin central government sought to minimize the role of aristocrats and landowners and have direct administrative control over the peasantry, who comprised the overwhelming majority of the population, and control over whom would grant the Qin access to a large labor force. This allowed for the construction of ambitious projects, such as a wall on the northern border, now known as the Great Wall of China.

he Qin dynasty introduced several reforms: currency, weights and measures were standardized, and a uniform system of writing was established. An attempt to restrict criticism and purge all traces of old dynasties led to the infamous burning of books and burying of scholars incident, which has been criticized greatly by subsequent scholars. The Qin's military was also revolutionary in that it used the most recently developed weaponry, transportation, and tactics, though the government was heavy-handed and bureaucratic.

Despite its military strength, the Qin dynasty did not last long. When the first emperor died in 210 BC, his son was placed on the throne by two of the previous emperor's advisers, in an attempt to influence and control the administration of the entire dynasty through him. The advisors squabbled among themselves, however, which resulted in both their deaths and that of the second Qin emperor. Popular revolt broke out a few years later, and the weakened empire soon fell to a Chu lieutenant, who went on to found the Han dynasty. Despite its rapid end, the Qin dynasty influenced future Chinese empires, particularly the Han, and theEuropean name for China is thought to be derived from it.

Qin dynasty, also spelled Kin, Wade-Giles romanization Ch’in, ![Terra-cotta soldier [Credit: © yang xiaofeng/Shutterstock.com]](https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/blogger_img_proxy/AEn0k_tJqwectPAq3q86znulECTnNvO0L7q_wA_nS0xN4V3NgOzDztj04WLtx1sqJ_zLz3BwxsSY3O1n64cEU7G0TtwN_1PtpkozL5IKasqQsM15JjegyGld0NyCLCtPEVF0X3iZEooJmAgpsLkz8mB_K85DEykn3XSPXhvXblFKH0CcuSRLgXymZLa93UomKA=s0-d) dynasty that established the first great Chinese empire. The Qin—which lasted only from 221 to 207 bce but from which the name China is derived—established the approximate boundaries and basic administrative system that all subsequent Chinese dynasties were to follow for the next two millennia.

dynasty that established the first great Chinese empire. The Qin—which lasted only from 221 to 207 bce but from which the name China is derived—established the approximate boundaries and basic administrative system that all subsequent Chinese dynasties were to follow for the next two millennia.

The dynasty was originated by the state of Qin, one of the many small feudal states into which China was divided between 771 and 221 bce. The Qin, which occupied the strategic Wei River valley in the extreme northwestern area of the country, was one of the least Sinicized of those small states and one of the most martial. Between the middle of the 3rd and the end of the 2nd century bce, the rulers of Qin began to centralize state power, creating a rigid system of laws that were applicable throughout the country and dividing the state into a series of commanderies and prefectures ruled by officials appointed by the central government. Under those changes, Qin slowly began to conquer its surrounding states, emerging into a major power in China.

Those harsh methods, combined with the huge tax levies needed to pay for the construction projects and wars, took their toll, and rebellion erupted after Shihuangdi’s death in 210 bce. In 207 the dynasty was overthrown and, after a short transitional period, was replaced by the Han dynasty (206 bce–220ce).

The Origins of the Empire

The Beginnings of the State of Qin

There are written accounts about the ancient history of Qin, but it isn't known if the accounts are accurate. It is said that Fei Zi was appointed rule over the city of Qin in the northwest. He is called the founder of the state of Qin.

In 672, Qin rulers tried to expand eastward. The Qin initially didn't attempt conquests of other states because they feared that tribes around them would attack them if a large army left.

The Legalism Philosophy of Yang

Then Shang Yang came to power as a court official in 361. During the two decades that he ruled, he made big political changes that took hold. He espoused and ruled according to a defined set of strict rules and a clear political philosophy.

He was eventually killed, but his philosophy that was called Legalism was adopted by the ruling court. Shang Yang introduced a lot of major governmental and political reforms that were revolutionary for his time, and set the course for Qin to become militarily more powerful and more ruthless than the other states.

There was a generally known protocol for warfare in the whole Zhou region until Yang came to power that was somewhat similar to European ideas of chivalry in combat. There were ideas such as generals should allow the opposing generals to set up battle formations before beginning battle and other ideas like that.

There were also generally accepted family ties and responsibilities such as those espoused by Confucians. Shang Yang did away with the protocols and morals. He wanted subservience to the ruling court to be the foremost law, and to destroy enemies ruthlessly.

He also wanted everyone to be treated equally under a fixed set of laws. In a way, this legal system was fair because it was less arbitrary. He thought that everyone should be ruled by the same laws whether they were members of a ruling clan or a peasant.

Under Legalism, political opposition was not tolerated. One of the strengths of Qin was the tight central control.

An Offensive Buildup

To increase production, Yang privatized land, rewarded farmers who exceeded harvest quotas, enslaved farmers who failed to meet their quotas, and used slaves for his major construction projects to create better infrastructure.

He wanted to improve the transportation system so that the armies could move more easily and to enhance internal trade. He also emphasized the creation of large armies for military offense and the production of the best armaments. The technology advanced so that iron tools and weapons became common in Qin.

Instead of corps of dozens of chariots as were used previously, organized cavalry with masses of infantry became common. In the end, the Qin could muster armies of hundreds of thousands.

The new philosophy, weaponry, and construction projects made the large Qin armies ready for conquests.

Military Conquest and Expansion

In the year 269, a general of Zhao defeated two Qin armies. After this, Fan Sui became the chief adviser to the Qin ruler. He instituted Legalism-type policies and advocated attacking the other states and killing off their people.

They started preparing for major conquests. Qin rulers had an advantage in that their territory was in the far west of the Warring States region sheltered behind mountains with passes that could be defended.

Sheltered in their territory, for a about a generation they focused on building up their army and settling the land to provide food for their expeditions and to create wealth. They forced the people to build the Wei River Canal, Dujiangyan, roads and other projects and to be soldiers.

King Zheng (260–210) started to rule in 246 BC when he was 13. During a short period of time, his ruling court mobilized Qin for conquests and then started invading the other states.

Several of the states surrendered instead of fighting. In 230, Han surrendered to Qin. They defeated Wei in 225. In 223, they succeeded in conquering Chu after a major defeat. Chu also had a large army and a lot of territory, but they were surprised by a sudden attack. In 222 BC, Qin conquered Yan and Zhao. In 221 BC, Qin conquered the last state called Qi.

The Beginning of the Qin Empire

In this way, in only 9 years the Qin court gained the empire. King Zheng named himself Qin Shi Huang. His name means he was the first emperor and god of the Qin Empire.

The centralization of power and the standardization of the different peoples they conquered was their priority. The Legalism philosophy of Qin Shihuang justified strict rule to increase the empire's strength and the dominance of the emperor and his top rulers. They wanted to standardize even the people's thought, believing that standardization and the squelching of any dissent against the rule of the court would promote their power.

No comments:

Post a Comment